When I was a more righteous Muslim, I used to pray five times a day. Islamic prayers require you to recite surahs (chapters) from the Quran. One of the shorter ones is called Asr, which translates to “Time”1:

By time,

Indeed, mankind is in loss,

Except for those who have believed and done righteous deeds and advised each other to truth and advised each other to patience.

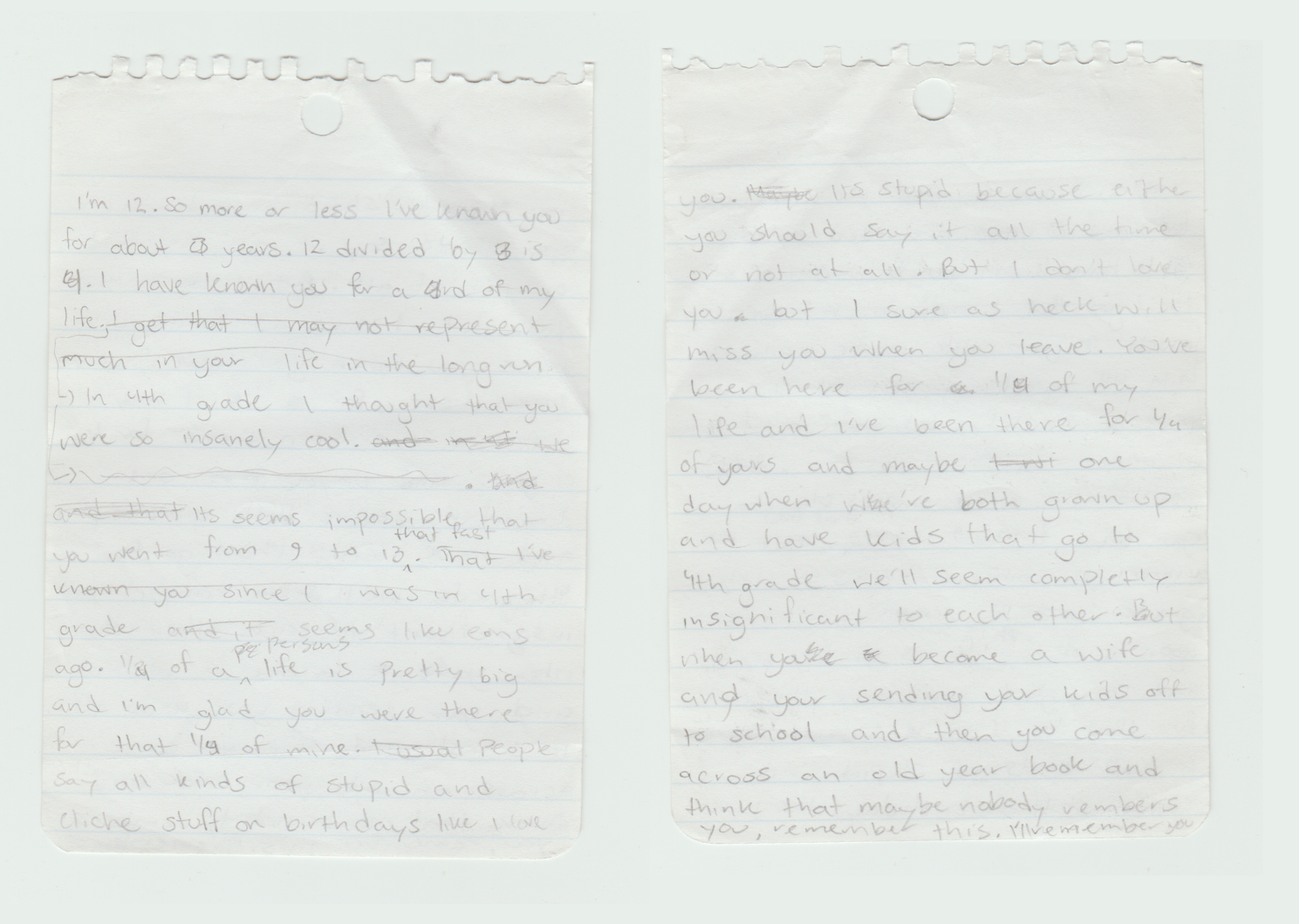

I used to think of a friend when I recited surah Asr. We met when I was nine. When I was twelve and she was turning thirteen, I wrote her a birthday card. I still keep a draft of it:

People say all kinds of stupid and cliche stuff on birthdays like “I love you”. It’s stupid because either you should say it all the time or not at all. But I don’t love you. But I sure as heck will miss you when you leave. You’ve been here for a quarter of my life and I’ve been here for a quarter of yours and maybe when we’re both grown up and have kids that go to fourth grade we’ll seem completely insignificant to each other. But when you become a wife and you’re sending your kids off to school and then you come across an old yearbook and think that maybe nobody remembers you, remember this: I’ll remember you.

She switched schools after that year, and - as it often happens - our friendship atrophied into something between estrangement and acquaintanceship. I saw her once when we were seventeen. She told me she kept the card I gave her in her locker. It felt like a strangely heavy confession - despite years of silence, I lingered in her life as an old card behind a metal door.

The part of surah Asr that was heaviest to me wasn’t the final verse - it was the very first: By time. I was seventeen. What does a seventeen-year-old know about eternity? All I knew of time was what I could feel of it. And I felt it most when I thought of her.

Yes, of course you should be patient, truthful, and righteous - everyone knows that. But when I heard it as: As real and weighty as that friendship was, let this be just as true: you must be patient, you must be truthful, you must be righteous - the words took on a new urgency.

One of my first jobs was at an Islamic summer camp where I taught a group of four- and five-year-old boys. Their little bodies were always aching to scramble, tussle, and tumble - and I was horrifically incompetent at subduing them. One day, they were being particularly rowdy, and I felt particularly helpless. Another counselor walked over. I was sitting down and she was standing above me when she asked, “Need some help?” When I would read verses about God’s overwhelming mercy and find myself unable to imagine what that might look like, I thought of her - standing above me, appearing out of nowhere, lending me a hand.

When a Muslim dies, a special funeral prayer called a Janazah is held. By the time my mom passed, I hadn’t prayed in a long time. But at her Janazah, I was thinking about a surah called Al-Kawthar. There’s a story behind how it was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH):

Anas ibn Mālik said, “While we were with the Messenger of God in the Mosque, he dozed off into a slumber. Then he lifted his head, smiling. We said, ‘O Messenger of God! What has caused you to laugh?’ He replied, ‘Verily, a sūrah was revealed unto me.’” Then he recited the sūrah and said, “Do you know what Kawthar is? It is a river that my Lord has promised me, and it has abundant goodness. It is a pool to which my community (ummah) will be brought on the Day of Judgment. Its containers are as numerous as the stars in the sky.”2

While I was in sujood - the position of prostration - I pictured that river. I imagined a shady tree beside it. And I imagined my mother as a teenager, her skin smooth like in the old photos, her face light and unburdened, sitting beneath that tree by Kawthar.

Joseph Campbell said that it is hard to love a perfect God 3. It’s Christ on the cross, he said, that becomes lovable.

Joan Osborne’s portrait of God as “just a stranger on the bus” is that same Christ on the cross to me. I suppose I have a particular affinity for that image, having had my share of lonesome late-night rides home on the subway. We’ve all felt like strangers at some point. To imagine God as that same kind of alienated figure, wounded in a way that is all too familiar, evokes something soft in me 4.

What if God was one of us?

Just a slob like one of us?

Just a stranger on the bus

Tryna make his way home

Osborne’s image of God isn’t so far from the portrait drawn by the 16th-century Jewish mystic Isaac Luria. Luria taught that before creation, there was only Ein Sof. In order to make space for the world, Ein Sof had to perform an act of tzimtzum or - the self-exile of Ein Sof from Himself 5. For a 16th-century Jew, well acquainted with exile, it was comforting to imagine that God, too, had known alienation.

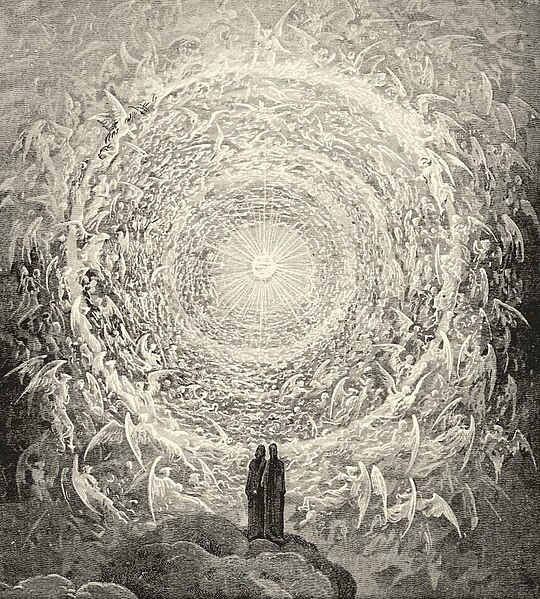

At the end of Paradiso, Dante finally reaches the Empyrean. There is light and mist but no real geography: Heaven is the realm of the ineffable6. He sees God. He fails to speak.

God, eternity, life after death - I don’t have a hope of ever understanding them except through approximation. Eternity, of course, is not really like a childhood friendship. God’s mercy is not quite like the relief of a camp counselor offering help. Heaven is not a tree by a river, and God is not a stranger on the bus.

For a long time, I tried to love God as I had when I was more devout. When I was a practicing Muslim, my life had never felt so meaningful. I felt soft and tender, always thinking about how to best live my life in service of something higher. Always trying so earnestly to be good.

Even after my beliefs changed, I kept trying to pray. Not because I thought it would get me to heaven, but because I missed the sense of purpose it gave me. I tried again and again to recapture that feeling. But it never returned. I felt something like grief instead.

So if God is not Christ on the cross, or a stranger on the bus, or a counselor, or a king building the heavens and the earth in seven days - if God is not Someone, not even Something 7, then what is left? And how do you love what remains?

You don’t.

When you chant AUM, the sound travels through the mouth: it begins in the back (ah), moves to the center (oo), and ends with the lips closed (m). You can feel the reverberation slip into silence before arising again. Birth, life, death - to birth again8. It is always accessible. It is always there.

God is like that - immanent and present in the familiar. Not a being, but the source of being - not chronologically, but ontologically. Creation is not something that happened once, at some point in time, but the condition of our being: Our dependency on something beyond us9. You don’t have to call that something God, but, to paraphrase Martin Buber, where would you find a word with quite the same magic? 10

You don’t love this kind of God the way you love a God you can pray to. That’s just not the point. You don’t have to “die for the metaphor.” 11 You don’t tear your hair out over the metaphor and you don’t love the metaphor with so much emotion it borders on fear. You observe it. You know it. And that’s all. You look inward, you look outward, and you understand that that’s God - immanent, intimate, familiar. You are the stranger on the bus and God, as incomprehensible as He is, is present through you.

Footnotes

The popular 1997 Saheeh International version translates it this way at least. There are translations, such as Seyyed Hossein Nasr’s The Study Quran, that instead translate it as “The Declining Day”↩︎

Sunan Abu Dawud 4747, Sunan an-Nasa’i 904, Sahih Muslim 400a↩︎

Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers, Power of Myth, 9.↩︎

In his profile on Julien Baker’s song Claws in Your Back, poet Hanif Abdurraqib expresses a similar sentiment: “The best love songs to God are the ones that divide the idea of God into whatever listeners think they can digest. I believe in God sometimes, but I believe in God the most when I imagine a God who has my mother’s laugh.” Baker coincidentally (and wonderfully) covered Osborne’s One of Us at a concert in New Zealand back in 2017.↩︎

Karen Armstrong, A History of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, 267.↩︎

Chapter one of Margaret Wertheim’s The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace: A History of Space from Dante to the Internet details the medieval Christian conception of body- and soul-space (in contrast to our modern materialist assumptions about space) through Dante’s The Divine Comedy. She writes, “The message—both concrete and metaphorical—is that in the presence of God we reach not only the limits of time and space, but also the limits of the language. Heaven might be the apotheosis of medieval soul-space, but precisely because of its perfection it is ultimately beyond human words. This is the realm of the ineffable.”↩︎

Author and poet Garret Keizer might not take kindly to this assessment of God being closer to Nothing than Something. He writes in his essay The Courtesy of God for Lapham’s Quarterly, “That said, I am more at ease with atheists than with sophisticated theists. I mean those people who say that God is far too big to care about their little woes, usually meaning that they are far too smart to fall for any such baloney. They are beyond anthropomorphism. They can spell anthropomorphism. For them God is sort of like a force—“whatever it was Einstein meant when he spoke of God,” as if they have a prayer of ever knowing. It is a most peculiar smugness.”↩︎

Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers, Power of Myth, 117. I am most certainly doing a disservice to the concept of ‘AUM’ here as it represents much more than just the cycle of life.↩︎

David Bentley Hart, The Experience of God: Being, Consciousness, Bliss. By not qualifying any of these statements, I am asking the reader to make a big jump in logic but I intend to qualify at least some of them in a later post.↩︎

Karen Armstrong, A History of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, 387.↩︎

Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers, Power of Myth, 117.↩︎